Choline: The Nutrient You Mightn’t Have Known You Need

Choline was long underappreciated, but we are becoming more and more aware of just how crucial it is in many stages of life- from fetal development to advancing age. It has a key role in many areas of health- not least the production of the major neurotransmitter acetylcholine. It is an essential nutrient, along with the likes of omega-3 fatty acids and essential amino acids. While our liver can synthesise it (in the form of phosphatidylcholine) it does so in such inadequate amounts that we must consume it regularly to avoid illness. Let’s look at what you need to know.

Key Points:

- Choline has diverse functions throughout the body. Deficiency has been associated with birth defects, declining cognitive function, liver disease and more. More research is required to identify whether it causes these problems or is simply linked, and to delineate it’s role from other nutrients.

- It is an essential nutrient that has functional similarities to other nutrients such as folate. Our liver can only produce small amounts so we need to consume it regularly through meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy, vegetables, wholegrains, legumes, nuts and seeds.

- As animal products are the richest sources, vegans, vegetarians and highly plant-based dieters may need to consider supplements.

- There is a lack of clarity in the research regarding precisely how much we need to consume and how well the general public meets their needs.

What is choline and why does it matter?

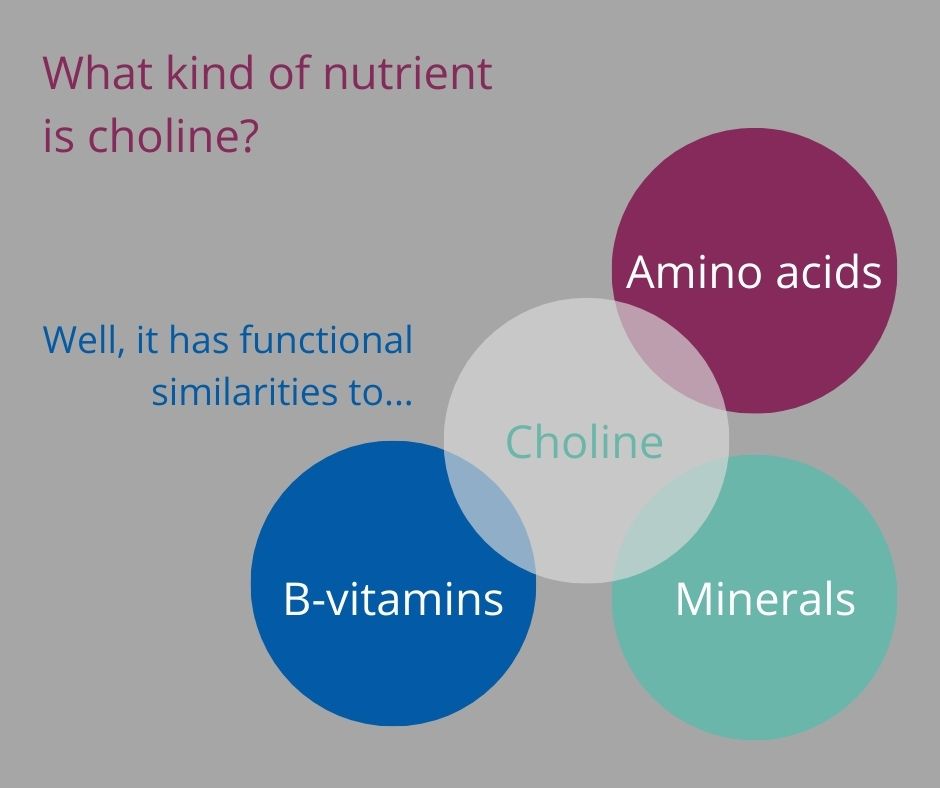

Choline is often grouped with the B-vitamins for simplicity’s sake, but it is actually tricky to classify… It has functional similarities to folate (vitamin B9) and other B-group vitamins, as well as minerals and amino acids.

Choline comes in several forms i.e. bound to other chemical groups. There are fat-soluble choline forms (i.e. phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin) and water-soluble forms (phosphocholine, glycerolphosphocholine, and free choline). These are all available in different foodstuffs… but the relevance of the form of choline you consume is not completely understood. For example, there is a lack of information on their relative bioavailabilities (how well they are absorbed and used by the body).

Also, animal studies have shown that how animals use different forms of choline varies according to lifestage… but this has not yet been proven in humans.

The overlap in function between choline and other nutrients is often not accounted or controlled for in the research. This means it’s tricky to make definitive delineations and conclusions about the roles and importance of choline.

Nonetheless, it seems to have diverse roles in health:

- As a precursor to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, it helps to transmit signals throughout the nervous system. It can therefore affect memory, mood, muscle control, and other functions

- It’s crucial to early brain development

- Precursor to key phospholipids found in cell membranes (phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin), thus providing structural integrity to cells

- Affects the signals sent across a cells’ membrane

- Involved in transport and metabolism of lipids (fats)

- Can affect gene expression

Complications of inadequate choline levels

Hard evidence is limited, however… There are associations with problems such as birth defects, neurodevelopment and cognition alterations, muscle and liver damage, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer. We look at a few in more detail here.

Choline and prenatal development

Pregnant women and their babies are particularly at risk of choline deficiency, with far reaching consequences.

Choline is able to donate part of its structure (its methyl groups) to DNA molecules. This can change the activity of a DNA sequence. As a result, low levels of choline among expectant mothers have been linked with neural tube defects, cleft lip, hypospadias, and cardiac defects and more.

Choline and cognition

Observational studies suggest a link between deficient choline levels and impaired cognition. Furthermore, it is thought that as a precursor to phospholipids found in cell membranes, phosphatidylcholine could enhance neurons’ structural integrity, and therefore brain function. Choline can also affect gene expression within neurons. Whether this is a causal link is quite another question. So far, animal studies provide some support, but human research has not consistently shown that increased intake and/or blood levels of choline improve neurological function in healthy adults.

Choline status may even have a role in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. It has been observed that the brains of people suffering with Alzheimer’s disease have less of the enzyme that converts choline into acetylcholine. However, as yet there is little supportive that consuming higher levels of phosphatidylcholine could reduce the progression of such diseases. Perhaps future research will reveal if targeting other parts of the conversion pathway between choline and acetylcholine could be effective.

Choline and liver health

There are clear associations between choline deficiency and liver damage. This may in part be due to its importance to maintaining cell membrane structure. In addition, the liver needs it for VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol. While excess VLDL increases deposition of plaque on arteries and therefore is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, low amounts mean that transport of fats away from the liver is impaired… potentially leading to fatty liver (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease). However, clinical studies have not indicated that choline can be successfully used to prevent or treat this disease.

What are healthy levels of choline?

It is thought that healthy levels of choline are between 7-20mmol/L. Yet in truth, choline is not a routine blood test for healthy people- so there’s some question about what are the ‘typical’ levels.

Research suggests that even if you’re fasting, the body maintains its levels at 50%+ of normal levels. It is unknown how this is ensured, but hypotheses include that the body adapts and breaks down cell membranes in order to maintain blood levels, or possibly ups its synthesis.

How much choline do we need in our diets?

There is literature out there… but I’d say we don’t actually know with any certainty. There are many variables. For one thing, how much you need will vary depending on how much folate (and methionine and betaine) is in your bod. Because of their overlapping roles, it is well established that if you’re folate deficient, you’ll need more choline and vice versa. People also differ in their innate ability to produce it themselves. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that there are several common variations in genes that can significantly alter an individual’s choline requirements.

Males and postmenopausal women seem to need more. It is that oestrogen might assist the body in synthesising it. Pregnant and lactating women also need more.

In the face of insufficient data, health organisations have settled on Adequate Intakes (AI’s). AI’s are average daily levels assumed to be adequate, compared to RDA’s/RDI’s which are based on more evidence and are designed to meet the needs of 97-98% of the population. To illustrate why we need to realise there are uncertainties surrounding these figures: the IOM based their AI’s on just one study where men who became deficient in choline and showed signs of liver damage. No women were involved in this study and only one dose was used. They estimated the AI for women and other age life-stage groups based only on recorded averages of body weights, or in the case of infants, the average amount provided in breast milk.

Anyway, if you still want to know what the current recommendations for adults from the US IOM (Institute of Medicine) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) are, here you go:

| IOM | ESFA | |

| Adult males | 550mg/day | 400mg/day |

| Adult females | 425mg/day | 400mg/day |

| Pregnant women | 450mg/day | 480mg/day |

| Lactating women | 550mg/day | 520mg/day |

Can you have too much?

Yes. Like everything, there is such a thing as too much. Side effects can include a fishy body odour, vomiting, excessive sweating and salivation, low blood pressure, possibly increased CVD risk, and liver toxicity. The available evidence suggests people above 14 years of age should keep their intake below 3500mg. 9-13 year olds below 2000mg, and children up to 8 less than 1000mg.

How to get choline into ya

Sources of choline include:

- Animal sources such as liver, beef, fish, pork, and chicken are richest as their cell membranes contain significant amounts of phosphatidylcholine

- Dairy foods also contain good amounts of total choline

- Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, brussels sprouts

- Red-skinned potatoes

- Some beans eg: soybeans

- Nuts, seeds, wholegrains

- In the US, lecithin, which is rich in phosphatidylcholine, is a commonly used to emulsify processed food, (eg: gravy, dressings, margarine)

- Also found in breast milk and many formulas

Supplements can also provide free choline or choline in combination with the B vitamins, or multivitamin/multiminerals. To date, we have no information comparing how well each of these forms are absorbed and used by the body.

The Verdict

Eating enough choline-containing foods daily helps ensure that our nervous system and cognition, metabolism, genes, liver and cell membranes function well. Pregnant women in particular need to pay attention to their choline intake, to minimise the chances of their children having birth defects.

There are a number of factors that can change how much an individual needs. Unfortunately, several weaknesses in the literature make it hard to know how much the ‘average’ person actually needs… or how much the population at large is taking in. Several studies claim that on average people don’t have adequate intakes of choline. I would dispute this, however, based on the lack of evidence underpinning AI’s. Surveys of dietary intakes often don’t involve representative samples of the population, and the food databases that intakes are compared against are not necessarily accurate. In Australia, we use data from global food databases, despite the fact that our food supply may differ.

Researchers of one study have stated that despite possibly deficient intakes in the US, actual deficiency in healthy people who aren’t pregnant, don’t have genetic differences and don’t receive all their nutrition via IV is rare.

Because the richest sources of choline come from animals, there is a school of thought that the movement towards plant-based diets could place choline at risk. Before you panic and reach for an extra chicken a day, however, you should reflect on your own dietary habits. Australian guidelines are that we should eat 1-3 serves of meat/chicken/fish/eggs/vegetarian protein sources per day. Do you take many of these serves in the form of 100g of fish, 80g of poultry, 65g of lean red meat, or 2 eggs? If so, you should be fine for choline. In fact, if intakes were uniform over the country, I could guarantee you have absolutely nothing to worry about. 2019 OECD data indicates that Australian’s consumed 19.7kg of beef and veal, 20.3kg of pork, 43.5kg of chicken and 6.2kg of sheep per capita… i.e. plenty.

If you are vegetarian, vegan or have a highly plant-based diet, though, you may want to consider supplements.

Perhaps the well-used balanced approach to eating is the best we can recommend, given the overlapping functions with folate and other nutrients. I.e. lots of variety, including vegetables and fruit, whole grains, nuts and seeds, and some dairy and high quality meat/eggs. That should meet all nutrient needs, and in turn reduce the bodies’ demand for choline.

What choline-rich foods do you eat regularly?

References

Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (2017, June 13). Lean Meat and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds and legumes/beans. Accessed at https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/five-food-groups/lean-meat-and-poultry-fish-eggs-tofu-nuts-and-seeds-and

Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (2015, July 23). Australian Dietary Guidelines 1-5. Accessed at https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines/australian-dietary-guidelines-1-5

Derbyshire, E. (2019). Could we be overlooking a potential choline crisis in the United Kingdom? BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health 2. Doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2019-000037

EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies), 2016. Scientific opinion on Dietary Reference Values for choline. EFSA Journal 2016; 14(8):4484, 70 pp. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4484

National Institutes of Health. (2020, July 10). Choline: Fact Sheet For Health Professionals. Accessed at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Choline-HealthProfessional/

OECD (2020), Meat consumption (indicator). doi: 10.1787/fa290fd0-en (Accessed on 09 December 2020)

Probst, Y., Guan, V., and Neale, E. (2019). Development of a Choline Database to Estimate Australian Population Intakes. Nutrients, 11(4), 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040913

Wallace, T.C., Blusztajn, J.K., Caudill, M.A.,et al. (2018). Choline. Nutrition Today. 53(6):p 240-253. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000302

Wiedeman, A. M., Barr, S. I., Green, T. J., Xu, Z., Innis, S. M., and Kitts, D. D. (2018). Dietary Choline Intake: Current State of Knowledge Across the Life Cycle. Nutrients, 10(10), 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10101513