Turmerosaccharides Benefits: Sweet for Joints

Move over curcumin and whole turmeric, turmerosaccharides are so hot right now. Research into this component of turmeric has ramped up over the last few years. The truth is research is still in its infancy- in contrast to curcumin, which has a reasonable body of research. But, the promising results so far have seen it embraced as a potential treatment for that right pain in the knee (and other joints), osteoarthritis. Here is what we do know.

Key Points:

- Turmerosaccharides are complex carbohydrates which are naturally present in modest amounts in turmeric, but available in higher levels in the patented product Turcamin.

- Limited studies suggest turmerosaccharides can reduce knee inflammation, pain and improve function and mobility.

- A reduction in proinflammatory molecules, increase in anti-inflammatory molecules, and support of collagen and glycosaminoglycans likely mediates its tangible effects.

- We as yet do not know what is the optimal dose.

What are turmerosaccharides?

Basically, turmerosaccharides are polysaccharides or complex carbohydrates unique to turmeric. Their health-promoting properties (see below) might give staunch anti-carbers pause for thought. They can and should play a valuable part in a balanced diet. (Just saying…)

Turmerosaccharides do compose a relatively small amount of whole turmeric, and so they have largely been studied in the form of Turmacin (more robotically known as NR-INF-02). Turmacin is a patented turmeric extract which is rich in turmerosaccharides (12.6% by weight). It also has minimal curcumin, which allows scientists to accurately attribute any effects to turmerosaccharides.

Turmerosacharides could help manage osteoarthritis… and improve joint function generally

The idea that turmerosaccharides help can help with osteoarthritis comes from a limited number of animal and human studies- of modest size.

In one study, rats were given osteoarthritic-like pain in a knee by injecting it with a substance that results in a disruption in metabolic processes and eventual death of chondrocytes (cartilage cells). It was found that feeding the rats a turmerosaccharide rich fraction of Turcamin reduced their pain for 24 hours afterwards. The effect may have persisted for longer but no measurements stopped at that point. If you’re wondering how they knew that the rats experienced less pain: they didn’t ask the rats, but rather looked at weight redistribution from the injured leg to the uninjured. The ability of an injured limb to bear weight is accepted as an objective marker of pain.

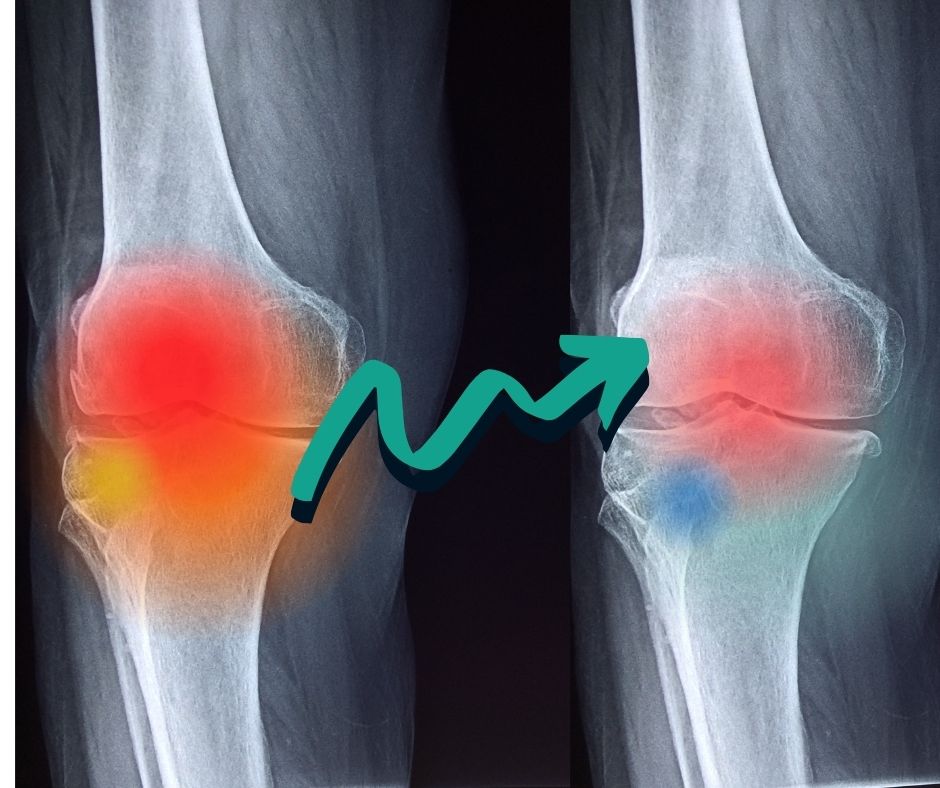

| Osteoarthritis occurs when the cartilage on either side of a joint wears down, causing bones to come into direct contact with each other- which often is accompanied by pain and inflammation. |

A randomised controlled trial among 90 healthy people found that turmerosaccharides reduced the subjectively experienced pain resulting from 10 minutes of strenuous exercise. In addition, range of motion was increased by approximately 5 degrees, which is significant (3-4 degrees is considered minimally clinically important). There was also a trend towards preserved muscle contraction force (which tends to decrease with inflammatory pain). The authors of this study suggest that in this situation, turmerosaccarides may be a superior anti-inflammatory to curcumoids, which has been proven to improve subjective indicators only. However, the comparison hasn’t been exhaustively studied to allow definite conclusions.

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted on healthy people, so the findings can’t be applied directly to people with osteoarthritis. However, strenuous exercise does put stress on knee chondrocytes, leading to upregulation of proinflammatory molecules such as metalloproteinases (MMP’s), tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukins and various aggrecanases. Such molecules are also implicated in inflammation associated with osteoarthritis.

There is one randomised controlled study where 120 patients with osteoarthritis displayed improvements to joint pain and function with Turmacin use. This was according to both subjective and clinical assessments. In addition, people taking Turmacin relied less on ‘rescue’ medication to deal with flare-ups in pain.

How do turmerosaccharides work?

As you may have gathered, reduced inflammation is thought to be key to turmerosaccarides benefits in regards to joint function and osteoarthritic pain.

Cartilage cell culture studies suggest turmerosaccharides inhibit proinflammatory molecules (eg: cyclooxygenase, prostaglandin-2, interleukin-2) and increase anti-inflammatory molecules (eg: interleukin-10), and reduce cell toxicity and death. Meanwhile, they’ve shown an increase in the expression of the gene for type II collagen and have a protective effect on glycosaminoglycans. These are key proteins providing structural integrity to cartilage, and help lubricate joints, respectively. Quite logically, this is believed to create an improved balance between the cartilage breakdown (catabolism) and build-up (anabolism).

What dose of turmerosaccharides should you aim for?

Because the research is still very young, we are unable to suggest appropriate doses.

The study on simulated osteoarthritic pain among rats found that a higher dose of turmerosaccharides provided more, and longer lasting, pain reductions. However, this does not provide information on what are appropriate doses for humans.

The study that showed that turmerosaccharide supplements improve knee range of motion and reduce pain in healthy people upon performing strenuous exercise does not provide clear information on whether less is more or more is more. I wouldn’t have predicted the pattern of differences between people who took 0.5g and 1g per day, for 84 days. This may have been due to the small numbers of participants, so larger studies are required.

Safety is another consideration in choosing doses. Four of the 90 healthy people taking either 0.5 or 1g per day of Turmacin experienced indigestion. Another study, published in just August of this year (2020), found that healthy people generally tolerated 1000mg or 2000mg of Turcamin for 84 days. Some mild-moderate adverse events were observed that may have been related to the supplement, but they can neither be definitively attributed to the supplement or not. For this reason- and the fact that only 48 people participated in the study- further research is warranted. It is also important to assess the safety of turmerosaccharides for people who do not enjoy good health.

The Verdict

While there is only limited research as yet, it appears that turmerosaccharides could improve osteoarthritis symptoms and improve joint function (for both people with osteoarthritis and without). It appears generally safe, at least in the short term, with only mild-moderate side effects reported thus far. To achieve a clinically significant effect supplements may be required, but we as yet do not know what the optimal doses are, in regards to either benefit or risk.

Have you tried turmerosaccharides? Let us know about your experience!

References

Basham, S.A., Waldman, H.S., Krings, B.M. et al. (2020) Effect of Curcumin Supplementation on Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Muscle Damage, and Muscle Soreness. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 17(4):401-414, DOI: 10.1080/19390211.2019.1604604

Bethapudi, B., Murugan, S., Illuri, R., Mundkinajeddu, D., and Velusami, C. C. (2017). Bioactive Turmerosaccharides from Curcuma longa Extract (NR-INF-02): Potential Ameliorating Effect on Osteoarthritis Pain. Pharmacognosy magazine, 13(Suppl 3), S623–S627. https://doi.org/10.4103/pm.pm_465_16

Chandrasekaran, C. V., Sundarajan, K., Edwin, J. R., Gururaja, G. M., Mundkinajeddu, D., and Agarwal, A. (2013). Immune-stimulatory and anti-inflammatory activities of Curcuma longa extract and its polysaccharide fraction. Pharmacognosy research, 5(2), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8490.110527

Madhu, K., Chanda, K., and Saji, M.J. (2013) Safety and efficacy of Curcuma longa extract in the treatment of painful knee osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Inflammopharmacol 21:129–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-012-0163-3

Raj, J.P., Venkatachalam, S., Racha, P., Bhaskaran, S., and Amaravati, R.S. (2020). Effect of Turmacin supplementation on joint discomfort and functional outcome among healthy participants – A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 53:102522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102522

Selvi, M., Mohan M.R., Bethapudi, B., Mundkinajeddu, D., and Kumari, S. (2020). Safety of NR-INF-02, an Extract of Curcuma Longa Containing Turmerosaccharides, in Healthy Volunteers: A Randomized, Open-label Clinical Trial. Alternative therapies in health and medicine, AT6360. Advance online publication.

Velusami, C.C., Richard, E.J,. and Bethapudi, B. (2018) Polar extract of Curcuma longa protects cartilage homeostasis: possible mechanism of action. Inflammopharmacol 26: 1233–1243 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-017-0433-1