Collagen Care: Eating Your Way to Healthy Skin

Protecting and replenishing collagen is a common goal of anti-ageing skincare. As we’ve seen, the cosmeceutical industry has thrown a whole bunch of products at this aim, using ingredients ranging from collagen hydrolysate to vitamins C, E, and B3, retinoids, phytoestrogens, and other botanicals. While such topical applications and supplements have potential, another influence that can’t be overlooked is your diet. What you routinely put in your gob is bound to affect your skin. In this final installment of our series on collagen, we look at what nutritional tweaks may help support collagen replenishment, and the evidence behind them.

Key Points:

- Regular protein intake, as well as quality of protein, is vital to maximise the health of collagen within your skin. Based on collagen structure and/or investigative studies, it would appear that the amino acids lysine, proline, glycine, BCAA’s, and essential amino acids generally are particularly important, however the proof is sadly limited.

- Eating the carotenoids lycopene, lutein and ꞵ-carotene through whole fruit and vegetable products may protect collagen from degradation.

- Consuming vitamins C and E in combination with other antioxidants could offer substantial protection to your collagen, but there is a question mark over what doses are appropriate to maximise benefits without risking harm.

Why your munchables matter

The old adage that ‘you are what you eat’ is as true for your skin as it is for your spleen. Topical applications can be helpful- particularly for the epidermis, which does not receive nutrients and other goodies directly from the blood supply. Yet topical applications are often not very effective at passing through this outer layer of skin. The deeper dermis, however, does have a trusty blood supply. Therefore the nutrients you consume are likely to reach it.

Some caveats are that there are limits to how much of a nutrient can be absorbed into the bloodstream, and the nutrients in your bloodstream don’t preferentially get delivered to the skin.

Your protein and amino acid intake will affect collagen

For all its special properties, collagen is just a protein. Therefore, If you don’t give your body enough amino acids (i.e. building blocks of protein), collagen synthesis is simply impossible. In this case the body will adapt by slowing down its collagen breakdown. While preventing the loss of collagen, the trade-off is that it gets older and in time will become less efficient. So you want to eat enough to encourage protein turnover, where old proteins are broken down and replaced with new, fully-functional ones.

It is not just the total protein you eat that matters. You also need to ensure all the amino acids that make up collagen are available, in appropriate amounts. Consuming collagen sources isn’t the only, or necessarily best, way to do this. As we’ve seen previously, collagen hydrolysate (from supplements) is not guaranteed to reach the skin.

What else, then, can you do?

Get your amino acid supply by eating a variety of quality protein sources. Keep in mind that each protein-containing food will have different amino acid profiles. Collagen contains 19 amino acids- i.e. all except cysteine, so it is important to cover (almost) all bases.

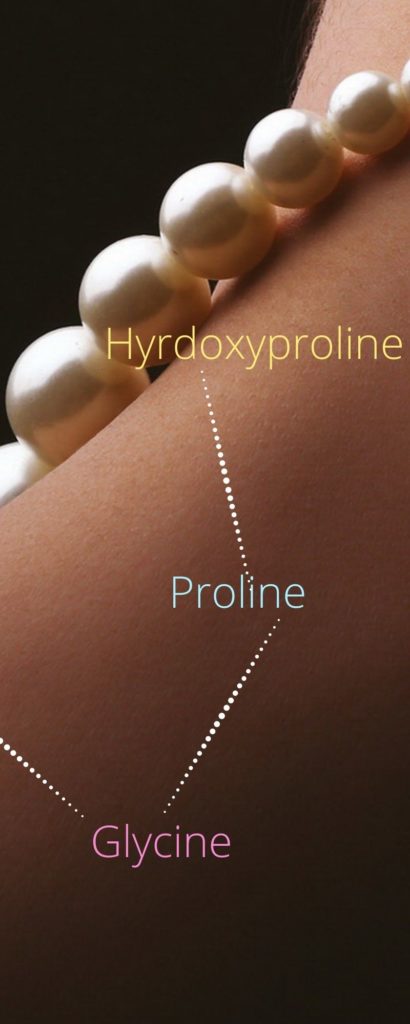

You also need to include good amounts of some ‘priority’ amino acids that characterise collagen. It is remarkably high in three: glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline. These often form a repeating sequence that allows collagen to take on the triple-helical structure that is central to its strength and viscoelasticity, i.e. its function in providing structural integrity to the skin. Collagen chains bend into their helical structure around glycine, the smallest amino acid out there.

The abundant presence of hydroxyproline, as well as (less-abundant) hydroxylysine makes collagen a unique protein. They are the ‘metabolic dead ends’ of proline and lysine, respectively. That is, they can’t be reused once collagen is broken down, and no more chemical reactions can occur to alter their form. They may just have to be discarded and fresh amino acids inserted into collagen.

However, you will not boost your potential for synthesising collagen by consuming ‘fresh’ hydroxylysine or hydroxyproline. Your body actually uses proline or lysine to build collagen. Once the framework of a collagen peptide has been fully built, proline and lysine are converted to their hydroxy-derivatives with the help of a specific vitamin-C dependent enzyme (hydroxylase). Thus, at least in this regard, eating collagen itself is unnecessary, even though it is a unique supplier of hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine.

It is possible for your body to synthesise glycine and proline (and therefore hydroxyproline) from other molecules as they are non-essential amino acids. But lysine is an essential amino acid, so you need to consume lysine in order for your body to produce hydroxylysine. (See table below for a breakdown of the essential and non-essential amino acids).

| Essential amino acids Histidine Isoleucine Leucine Lysine Methionine Phenylalanine Threonine Tryptophan Valine | Non-essential amino acids Alanine Arginine Asparagine Aspartic acid Cysteine Glutamic acid Glutamine Glycine Proline Serine Tyrosine |

While consuming good amounts of glycine, proline and especially lysine would therefore appear logical, there is actually limited research exploring the impact of specific amino acid intake on collagen synthesis within the skin. In fact I was unable to find studies exploring the impact of lysine intake. There was some research for other amino acids: cell culture studies have shown a stimulation of collagen synthesis when proline and proline precursors were provided. On the other hand, mice studies have shown that neither single amino acids or branched chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and valine) alone affected collagen production among mice whose skin had been subjected to UV-induced ageing. And yet pairing branched chain amino acids with proline and/or glutamine did. More research is required to determine the mechanisms here, and what, if any, relevance it is to humans.

Besides the above, much of the evidence people look to comes from studies on wound healing- in animals. While wound healing does also rely on collagen synthesis, it is known that the healing processes for UV-induced ageing and wounds are very different. So the results may not be representative. Nonetheless, since we’ve got little else, here it is: wound healing studies among rats found that when 85% of amino acid intake came from non-essential amino acids, collagen fibres were thinner, sparser and arranged in a less organised way… all of which are unfavourable for skin integrity and strength. Thus it suggests that essential amino acid intake may be very important.

This scarcity of research may seem odd given how much interest there is in collagen. Nonetheless, in the face of this scarcity, let’s look at where you can obtain a good intake of the above-mentioned amino acids, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO).

- Good sources of lysine: Meat (pork, beef, lamb, fish, chicken), egg, dairy, legumes (eg: chickpeas, broad means, lentils, mung beans, butter beans), dill leaves, red pepper, spinach leaves, apple, papaya, carob, amaranth, pistachio, beetroot, brussel sprouts.

- Good sources of proline: Meat (lamb, pork, chicken, beef, fish), eggs (particularly yolk), milk and cheese, soy protein isolate, cabbage, asparagus

- Good sources of glycine: Meat (lamb, chicken, beef, pork, fish), egg, legumes (eg: such as soy, lentils, chickpeas, butter beans, mung beans), some provided in dairy, nuts and seeds (eg: brazil nuts, hazelnut, pistachio, fennel seed, linseed and amaranth), coconut and carob

- Good sources of BCAA’s (leucine, isoleucine, valine): Meat (beef, chicken, lamb, pork, fish), eggs, milk and cheese, legumes (eg: beans, lentils, soy), nuts and seeds (eg: chia seeds, hazelnut, pecans, pistachios, pumpkin seeds), coconut, cocoa.

- Good sources of essential amino acids generally: Meat (chicken, beef, pig and sea bass), legumes (soybeans, lentils, butter beans, chickpeas), brazil nuts, pecan, linseed, pistachio, quinoa. However, it is important to have the complete complement of essential amino acids, in appropriate amounts, which means it is best to consume a variety of protein sources rather than relying solely on one.

As you can see, there are a number of foods (meats, eggs, dairy, some legumes, nuts and seeds) that are rich in more than one of these amino acid types. Other foods are good sources of individual amino acids. This underlies the value of a varied diet, particularly if you practice vegetarianism or veganism.

Aside from amino acids, there are other things you put in your gob and bod that impact on your skin’s collagen…

Eating carotenoids for collagen

Retinoid-containing cosmeceuticals aren’t the only way to get benefits…

Lycopene gives tomatoes their bright red colour and has antioxidant properties. Eating lycopene can reduce expression of collagen degrading enzymes (MMP’s). This has been shown in a small study of 20 healthy women, where 16mg provided daily for 12 weeks in the form of 55g tomato paste, and in a randomised controlled study using lycopene-rich tomato nutrient complex capsules. The latter study also reduced other markers of genetic damage from UV exposure.

However, lycopene alone may not be responsible for these effects. Studies have shown that the combination of lycopene with other tomato phytonutrients (eg: phytoene, phytofluene, lutein) increased protection against other markers of UV-damage. Granted, the effect on collagen has not been directly assessed, however it would be prudent to consume products derived from whole-tomatoes rather than supplements of lycopene alone.

More research is still needed about lycopene’s effects, the dosage required, and the optimal combination with other nutrients.

Lutein is present in vegetables such as green beans, spinach, or broccoli- although the colour of lutein is masked by the dominance of green chlorophyll in these veg. It too can interfere with MMP overexpression resulting from UV exposure. Information regarding appropriate doses is lacking, but including these vegetables as part of a balanced diet will provide many benefits beyond collagen.

ꞵ‐carotene can be converted into retinol within the body, with antioxidant and skin-protective effects. However, the effects of dietary ꞵ-carotene on collagen levels has only been explored in limited studies, and with conflicting results. A very small, not necessarily representative study showed that 30mg supplementation may have some benefits, but 90mg produced unwanted side effects such making the skin more sensitive to UV light. More concerning is epidemiological evidence that suggests long-term use of high-dose supplements can be risky, particularly in smokers and asbestos workers, whose already high risk of lung cancer can be further increased. Thus it is probably best to stick to food such as carrots, sweet potato, pumpkin, spinach to get modest amounts of ꞵ-carotene.

Eating vitamin C for collagen

Vitamin C is required for collagen synthesis (it helps the conversion of proline and lysine to their hydroxy-counterparts, and stabilises collagen’s structure), and can also protect it against oxidative damage from UV-irradiation. There are topical applications, but dietary intake of vitamin C is also important. Fortunately, it is widely available in various fruit and vegetables, besides the much-lauded orange.

It seems that adequate vitamin C consumption may help prevent collagen degradation, but there’s less support for any claims it can repair damage that’s already done.

It is also worth noting that increasing your vitamin C intake- through food or supplements- is likely only effective if your blood levels of vitamin C start low. If they are already normal, any extra you consume is likely to end up in your urine rather than your blood (and ultimately, skin).

Combining nutrients together makes collagen better?

The antioxidant effect of vitamin C is enhanced when it is combined with other active molecules, such as vitamin E. A study from way back in 1998 showed that neither vitamin C or E alone offered protection against photodamage, but daily supplements of 3g vitamin C and 2g vitamin E increased photoprotection by approximately 50%. Granted this study focused on damage in the form of sunburn, rather than collagen degradation, but remember that UV exposure is also responsible for ageing.

The benefit seems even greater when a variety of antioxidants are consumed together, such as vitamins C and E, carotenoids, selenium, and proanthocyanidins; vitamins C and E, pycnogenol, and evening primrose oil; or marine protein, vitamin C, grape seed extract, zinc, and tomato extract. Such mixtures may be obtained from supplements or mixed meals.

However, the doses of vitamins C, E and other substances obtained in supplements often greatly exceed recommended levels of intake… and have potential for side effects. For example, although it’s impossible to prescribe an upper limit for daily vitamin C intake, due to patchy data, the Australian and UK authorities have suggested that it’s prudent to consume no more than 1000mg (1g) a day. The US authority suggests a limit of 2000mg (2g) for adults.

Vitamin C is a water soluble vitamin with little potential for toxicity, as excess is excreted in the urine as opposed to stored in fat. And yet, there have been side effects observed from acute high doses. These include gastrointestinal complaints, metabolic acidosis (where too much acid accumulates in the body, and people experience symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, fast breathing and lethargy), and potential changes in blood coagulation. In addition, animal studies suggest it may increase oxalate excretion, which can lead to kidney stones- but the evidence of this amongst humans isn’t substantial. Among people with haemochromatosis, high vitamin C intakes are risky as it can increase absorption of non-haem (plant) iron, thereby increasing chances of organs being poisoned by iron overload.

Australia’s recommended upper limit for vitamin E is 300mg per day, and there have been some observed consequences of excess doses, such as increased haemorrhage and stroke in people with existing risk factors. However, the information on this is still incomplete.

The facts are, the data these upper limits are based on is reasonably old, and for several reasons there is a lack of research on the topic from this century to suggest that the limits should be reviewed. This leaves us in an uncertain position regarding whether consuming higher doses for skincare is wise or advisable. The age-old tactic of getting ‘normal’ amounts of these essential nutrients from a varied plant-based diet is the safest bet, and supplements should be considered only under medical suggestion and supervision.

Is there anything else?

There very well could be many other foods that boost your collagen levels. For example, phytoestrogens and botanicals as discussed previously. Drinking green tea may also help- its polyphenols have benefited animals, but the evidence from human studies is not conclusive.

The Verdict

What you eat undoubtedly affects the health of your skin, however there is unfortunately limited research explicitly exploring the impact of nutrition on collagen. Because of this, it is not advisable that you take it upon yourself to increase your intake of any food or nutrient supplement too dramatically. Aiming for a balanced diet that provides protein from a variety of sources including meat, dairy, eggs, legumes, seeds and nuts, and other plant sources can ensure you get adequate essential amino acids in general, and lysine, proline, glycine and BCAA’s in particular. This is worth doing as, although the research is limited, they may be essential as building blocks for collagen synthesis. Consuming a variety of whole fruit and vegetable products is also important, as the carotenoids, vitamin C and E and other antioxidants they provide may protect your skin from collagen degradation.

What are your favourite collagen-friendly foods?

References

Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council and NZ Department of Health (Updated 2017, January 23). Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand: vitamin C. Accessed at: https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/vitamin-c.

Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council and NZ Department of Health (Updated 2014, April 9). Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand: vitamin C. Accessed at: https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/vitamin-e

Cho S. (2014). The Role of Functional Foods in Cutaneous Anti-aging. Journal of lifestyle medicine, 4(1): 8–16. https://doi.org/10.15280/jlm.2014.4.1.8

Corsetti, G., Pasini, E., Flati, V., Romano, C., Rufo, A. and Dioguardi, F.S.. (2015). Aging Skin: Nourishing from the Inside Out, Effects of Good Versus Poor Nitrogen Intake on Skin Health and Healing. In Farage, M.A. et al. (eds.), Textbook of Aging Skin: DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-27814-3_135-1

Corsetti, G., Pasini, E., Romano, C., and Dioguardi F. S. (2015). Nutrition and skin healing, the role of nitrogen intake: is “from in” predominant on “from out”? Acta Vulnologica. 13(3):171-76

Costa, A., Pegas Pereira, E. S., Assumpção, E. C.,et al. (2015). Assessment of clinical effects and safety of an oral supplement based on marine protein, vitamin C, grape seed extract, zinc, and tomato extract in the improvement of visible signs of skin aging in men. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 8:319–328. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S79447

Dioguardi, F.S. (2008). Nutrition and skin. Collagen integrity: a dominant role for amino acids. Clinics in Dermatology. 28(6):636-640.

Fuchs, J., and Kern, H. (1998). Modulation of UV-light-induced skin inflammation by d-alpha-tocopherol and l-ascorbic acid: a clinical study using solar simulated radiation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 25(9):1006-1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00132-4.

Food Policy and Food Science Service, Nutrition Division, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). (1981) Amino Acid Content of Foods and Biological Data on Proteins. Accessed at: http://www.fao.org/3/ac854t/AC854T03.htm#partI

Goodsell, D. (2000) PDB-101 (Protein data bank) Molecule of the month: collagen. doi:10.2210/rcsb_pdb/mom_2000_4

Grether‐Beck, S., Marini, A., Jaenicke, T., Stahl, W., and Krutmann, J. (2017), Molecular evidence that oral supplementation with lycopene or lutein protects human skin against ultraviolet radiation: results from a double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, crossover study. Br J Dermatol 176: 1231-1240. doi:10.1111/bjd.15080

Lodish, H., Berk, A., Zipursky, S.L., et al. (2000). Collagen: The Fibrous Proteins of the Matrix. In Freeman, W.H. (ed.), Molecular Cell Biology, 4th edition. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21582/

Murakami, H., Shimbo, K., Inoue, Y. et al. (2012)Importance of amino acid composition to improve skin collagen protein synthesis rates in UV-irradiated mice. Amino Acids. 42: 2481–2489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-011-1059-z

Parrado, C., Philips, N., Gilaberte, Y., Juarranz, A., and González, S. (2018). Oral Photoprotection: Effective Agents and Potential Candidates. Frontiers in medicine. 5: 188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00188

Pullar, J. M., Carr, A. C., and Vissers, M. (2017). The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health. Nutrients. 9(8): 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080866

Rizwan, M., Rodriguez-Blanco, I., Harbottle, A., et al. (2011). Tomato paste rich in lycopene protects against cutaneous photodamage in humans in vivo: a randomized controlled trial. The British journal of dermatology. 164(1): 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10057.x

Tessari, P., Lante, A., & Mosca, G. (2016). Essential amino acids: master regulators of nutrition and environmental footprint?. Scientific reports. 6: 26074. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26074